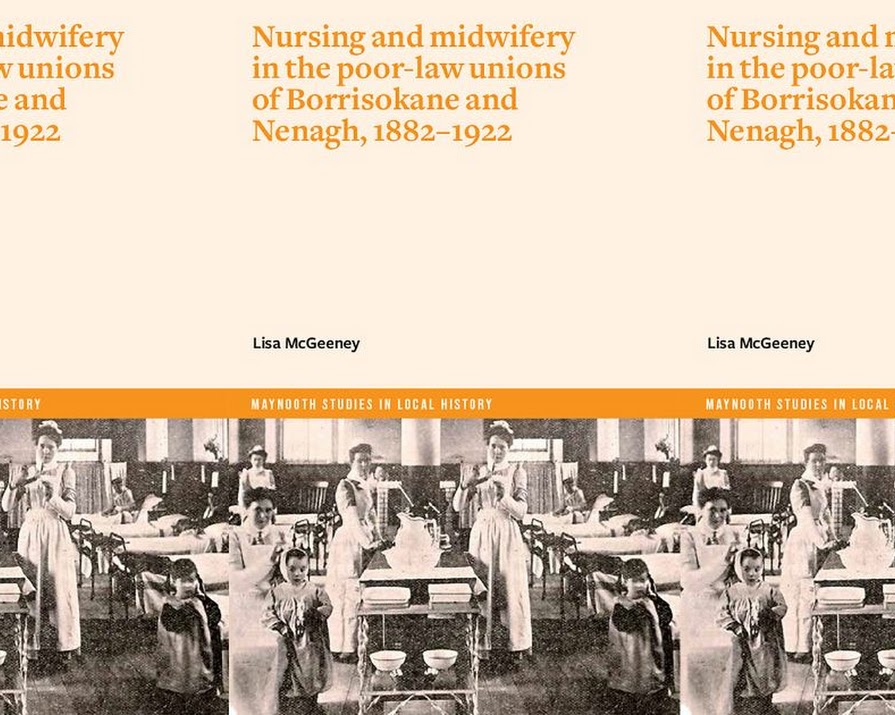

IMAGE Book Club: Read an extract from Lisa McGeeney’s examination of nursing and midwifery in the nineteenth century

By Sarah Gill

21st Nov 2022

21st Nov 2022

This week’s IMAGE Book Club title of choice is Nursing and midwifery in the poor-law unions of Borrisokane and Nenagh, 1882–1922 by Lisa McGeeney.

For this week’s instalment of our IMAGE Book Club, we’re sharing an extract from a study that examines how the professionalisation and development of nursing and midwifery in the nineteenth century was reflected in the poor-law unions of Borrisokane and Nenagh in Co. Tipperary between 1882 and 1922.

Differentiating between trained and untrained nurses and midwives, this book examines how each type of ‘nurse’ was perceived and who they were. The employment opportunities for these nurses and midwives were primarily in the poor-law medical relief services as dispensary midwives or as nurses within the workhouse infirmary and fever hospital.

Written by Lisa McGeeney — a registered nurse, midwife and public health nurse — she received a Masters degree in Local History from University of Limerick in 2020 and is embarking on a PhD in September 2022.

Advertisement

Read the extract below to get a taster for the rest of the book…

At the same time as the night nursing issue was being discussed, the board had other nursing problems with the fever hospital. The appointed nurse, Bridget Reynolds, had lived with her husband Michael, the workhouse schoolmaster, and their children Bridget Mary and John Thomas in staff accommodation in the workhouse compound until 1893. When Michael retired in that year, however, following more than twenty years’ service, he and the children were required to quit the workhouse and find lodgings in the town. They were permitted to visit Bridget, who lived in the fever hospital, but could not stay there. When Michael became ill in 1895 he returned to live with Bridget in her quarters so that she could take care of him but this was done without the knowledge of the master or the permission of the guardians.

Michael’s presence there became known only when Dr Minnitt was called to examine him. Bridget was brought before the board to account for her actions. They were not sympathetic to her explanation and called for her resignation in early June 1895. Michael died in the workhouse on 23 June 1895 aged 58 years old from chronic bronchitis and cardiac syncope. In an act of compassion, board member Thomas O’Brien proposed that Bridget be forgiven and her resignation be rescinded, which motion was carried. She had plans to leave soon to go to her sister in Australia but being able to retain her post in the meantime would ensure that she and her children had a means of support until then. Following further inquiries in August 1895, however, she was again asked to leave her post. The board were pleased to appoint Alice Cahalan, a qualified nurse and daughter of Dr Michael Cahalan, as fever hospital nurse in September 1895. Sadly, Alice would hold the post for less than a year before her untimely death from meningitis on 28 August 1896 aged 26 years. She died as a patient in Nenagh fever hospital. Her death was followed a few weeks later by that of the assistant nurse of the fever hospital, Margaret Flannery, who died in the workhouse infirmary from cancer of the breast, aged 40, on 30 September 1896. These deaths give credence to an unaccredited statement that was printed in the Nenagh News in 1896, warning of the risk posed to nurses, saying that ‘a healthy girl of seventeen, devoting herself to hospital nursing, dies on average twenty one years sooner than a girl of the same age moving among the general population’.

Miss Lavery, from Kilkenny, was then appointed to the post but resigned in August 1897 to take up a similar post in Roscrea union at an increased salary. For the next few years the posts of nurse and assistant nurse of the fever hospital were rolled over frequently. Nurse Lavery was replaced by Maria Hickey, who was in turn replaced by Letitia Fennelly, who left in 1899 for a job in Bandon union at a higher salary. When the post was advertised in 1900 at a salary of £25 per year with rations and apartments, it was also stated that ‘the number of fever patients treated in the last year did not exceed twenty-five’. Even with these low numbers, nursing in the fever hospital was arduous and potentially dangerous as exposure to infectious diseases left these nurses at risk of illness. At times when the fever hospital was free of patients the nurses worked in the main infirmary but when they had patients they were confined to the fever hospital and were not allowed near the main workhouse, infirmary, kitchen or any other buildings in case they spread disease. There were even complaints about them attending mass in town where they might spread disease to the congregation.

Another challenge that arose in the fever hospital was that when there was an outbreak of disease such as measles, scarlatina, typhus or similar then the two nurses appointed to the fever hospital were insufficient to do all the nursing that was required. For example, in 1894, an outbreak of typhoid fever in the town affected at least four Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) officers, leading to the death of Constable Follis. The district inspector, Mr Rogers, wanted another nurse available to care for the three policemen who remained in the hospital. The board had received a letter from Bridget Reynolds requesting an extra nurse to assist her as she was exhausted, but the chairman responded by saying that ‘Mrs Reynolds is a paid nurse, and she ought to do relay duty with her assistant; she ought to do either day or night duty’. This meant that each lady was expected to work a twelve-hour shift, day or night, seven days a week with perhaps only the assistance of a reluctant pauper nurse. The paupers sometimes refused to do the work, especially in the fever hospital, for fear of getting sick themselves. In 1882 three female paupers in Nenagh workhouse were charged at the petty sessions for their refusal to assist the fever nurse.

Pauper nurses were viewed as ‘the blackest spot on the poor-law administration’ and the sick poor deserved better. By 1896, the Irish Medical Association, church hierarchy and Irish Workhouse Association were calling for reforms that included the cessation of pauper nursing, employment of trained nurses, nurse training for nuns, better diets for all inmates, better care of the children in the nurseries, more humane conditions for elderly and infirm inmates and improved sanitary facilities. These reforms were supported by the LGB who instructed the boards of guardians that pauper nurses were prohibited in workhouse infirmaries under the Nursing Order of 1897 and that trained nurses were required in the infirmary under a further Nursing Order in 1898. The Nenagh board of guardians was reluctant to comply with these orders, claiming the increased cost as an unnecessary burden on the rate payers, which included themselves; nonetheless, from 1897 the number of nurses employed in Nenagh increased and more of them had the required training.

Advertisement

The first of the new recruits was midwife Margaret Turner, a 27-year-old widow with five children, from Dublin. Nenagh seems a long way to come from Dublin, especially as there were many maternity hospitals in Dublin but, as Julia Anne Bergin tells us, there was not enough employment in Dublin for the numbers of midwives being trained. The railway line in Nenagh might have influenced her decision, as it provided her with the fastest way of travelling between the city where her children lived and the town in which she lived and worked, for all except one of the children would remain in Dublin. She requested and was granted permission for her middle child, Alice Patricia, then aged 6, to live with her in her apartments in the workhouse. Over the next four years the nursing staff increased to four paid nurses as well as the community of five Sisters of Mercy.

Order your copy of ‘Nursing and midwifery in the poor-law unions of Borrisokane and Nenagh, 1882–1922’ by Lisa McGeeney for €12.95, right here.

Make sure you check back in later this week for a further insight into the life, times and writing processes of Lisa McGeeney with our Author’s Bookshelf interview…