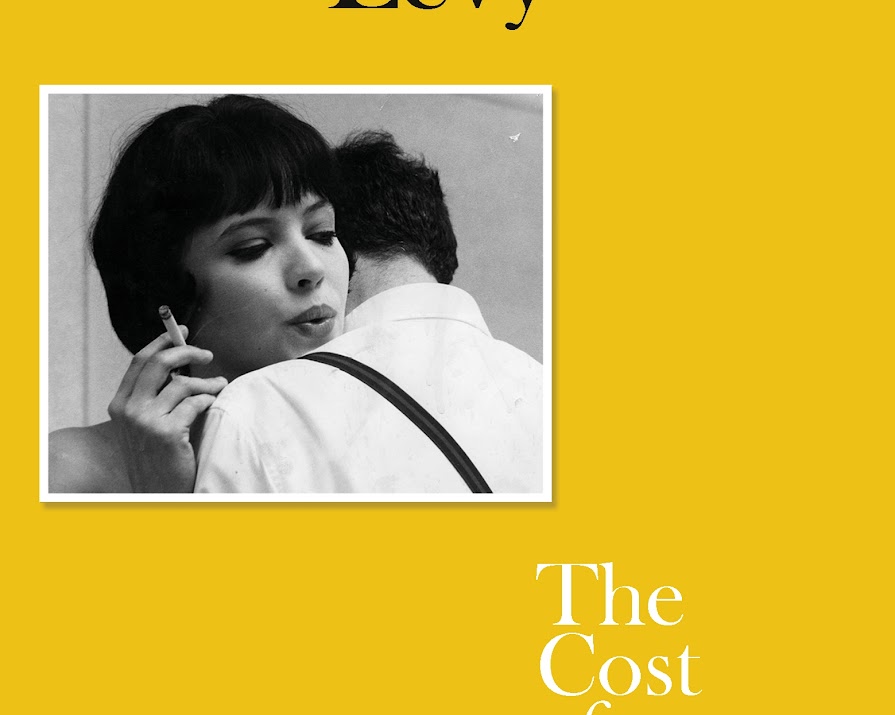

The Cost of Living review: divorce-lit for women who are fifty, alone and free

By Lia Hynes

15th Apr 2018

15th Apr 2018

‘The writing you are reading now is made from the cost of living’, says Deborah Levy in the final line of her latest book.

A memoir, her second, The Cost of Living, published this month, charts the author’s life after the break up of her marriage. Cost of living writing, as Levy terms it, charts the struggle of life.

She and her two daughters leave the family home, a suburban Victorian semi, and move into a rather bleak apartment block in North London. But there is a freedom in exiting ‘The Family House’, behind the creation of which Levy sees an ‘unthanked, unloved, neglected, exhausted woman’.

Levy skims over the details of her marriage’s decline, the book looks forward, as she creates ‘a new way of living’.

As a woman who has left her marriage, Levy sees herself as having stepped outside the norms laid down by the patriarchy. Her actions are a rejection of what society has outlined for her. Femininity, ‘as written by men and performed by women’, is no longer of use. It is an ‘exhausted phantom’, involving, for women, ‘sacrifice, endurance, cheerful suffering’.

Women, in Levy’s book, are often presented as ignored, overlooked or side-lined by men. Her best male friend refers to his numerous wives as wife, never by name, until after he divorces them. A colleague repeatedly forgets women’s names, deeming them wife or girlfriend ‘of’. Deborah herself rails against her own husband’s occupation of her mind, her thoughts are ‘full of Him’ in the angry aftermath of the marriage break down.

This is a tale of a woman fighting for her own identity. ‘Now that I was no longer married to society, I was transitioning into something or someone else. What and who could that be?’ she wonders. For Levy, marriage would seem to have stymied her creative voice. ‘To speak our life as we feel it is a freedom we mostly choose not to take’, she muses. The taking of this freedom is the mission which now ignites her. ‘I was thinking clearly, lucidly,’ she writes, ‘the move up the hill and the new situation had freed something that had been trapped and stifled.’

Levy is clear-eyed about what her new freedom entails though. Now fifty, she is alone, and free she muses. Free to support her family on an ageing computer, to pay all the bills. But the impression given is that the cost of being alone is favourable to what marital domesticity cost her.

Levy’s latest work sits within the canon of divorce memoirs such as Rachel Cusk’s Aftermath: On Marriage and Separation, Nora Ephron’s Heartburn, and Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love. Where chick-lit tends to focus on the trials and tribulations of the twenty-something singleton, divorce-lit, by its nature, will more likely deal with the process of recreating oneself in the aftermath of casting off the identity of wife.

While Levy’s new book is a meditation on rebuilding in the aftermath, Ephron’s Heartburn, an autobiographical novel based on the demise of Ephron’s marriage to her second husband journalist Carl Bernstein, tracks the immediate fallout after the miserable demise of the marriage. ‘Everything is copy’, after all, as the writer and director of Sleepless in Seattle famously said. Seven months pregnant, she discovers her husband is having an affair with an ‘unbelievably tall person’. She leaves, returns, before ultimately leaving again. Like Levy, she wrestles with finding her own voice, realising that in the very act of creating the family home, she has become a boring nonentity to her husband, and recounting how she feels as if nothing has happened to her since marriage. Her spouse, a writer of three weekly syndicated columns, takes ownership of all her anecdotes as fodder for his three weekly column and in doing so goes some way to erasing his wife’s experience of life. The Bernstein character agonising over whether he can get a column out of the salt and pepper shakers as a deadline looms is a particularly enjoyable passage.

Rachel Cusk’s Aftermath: On Marriage and Separation, is a bleaker affair. Whilst Levy’s work is a clarion call to women, and Ephron brings her signature wit to hers, Cusk’s book is a more difficult read. Life is now ‘a jigsaw dismantled into a heap of broken-edged pieces,’ she observes in the wake of her separation. Her writing is fascinating though on the complicated negotiations of a couple over the male and female parts of a marriage. ‘Call yourself a feminist’, her husband, who had left his job to be the children’s primary carer, taunts her at one point. ‘They’re my children..they belong to me’, she says during a conversation on custody.

Eat Pray Love, by Elizabeth Gilbert, is of course, the blockbuster version of divorce-lit. A juggernaut of a book, more a movement than a novel, Gilbert paid for the journey she recounts with an advance from her publishers. On turning thirty and finding herself crushed by depression despite her seemingly perfect life, Gilbert upends it all, eventually embarking on a year long solo journey, that would take her to Italy, India and Bali. It’s a relatively upbeat account of life after marriage, Roberts as the onscreen version of Gilbert is an unsurprising choice. Ultimately, Gilbert falls in love again (a relationship which has since come to an end). But, she tells her reader, ‘I was not rescued by a prince; I was the administrator of my own rescue’.

‘Being alone doesn’t suit you nearly as much as you think it does,’ a male friend tells Deborah Levy rather patronisingly at one point in The Cost of Living. But he is wrong. Being alone, and what they go through to get there, suits all these women, and they are fascinating in the telling.

The Cost of Living, Deborah Levy, Hamish Hamilton, RRP14.99