By Sarah Gill

15th Nov 2023

15th Nov 2023

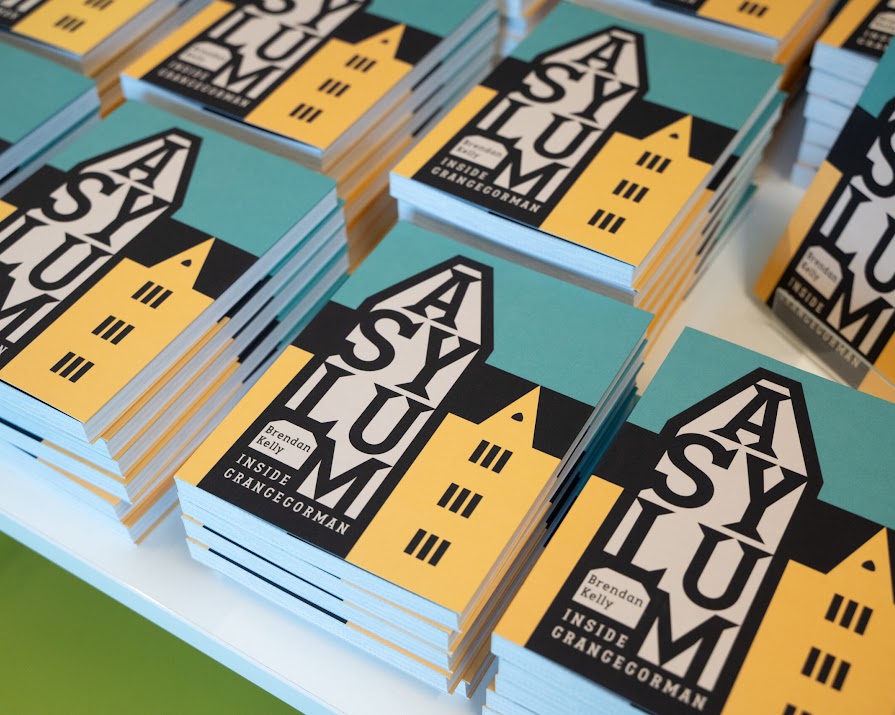

What was the life of a patient in an asylum really like? Through letters, medical records and doctors' notes, this book gives us a glimpse inside Grangegorman and the lives of those who lived and worked there.

This beautifully-illustrated book will make a thoughtful gift for anyone with an interest in history and mental health. On a given night in the 1950s, the number of people in Ireland’s psychiatric hospitals was more than double those in all our other institutions put together: prisons, laundries, mother and baby homes, industrial schools, orphanages.

Asylum: Inside Grangegorman is the story of just one of those places. Through newly-available letters, medical records and doctors’ notes, Brendan Kelly, Professor of Psychiatry at Trinity College Dublin, gives us a fascinating glimpse inside the institution formerly known as “The Richmond Lunatic Asylum” at Grangegorman and the lives of those who lived and worked there.

Read the extract below…

Mary G. was admitted to Grangegorman District Asylum in Dublin, Ireland’s largest mental institution, in early 1908. A 28-year old married woman with a baby of three months, Mary had refused food for the previous six days. Archival case-notes from the asylum record that Mary was paranoid. She ‘heard tapping at night. People followed her in the street…They said everything they could say’. At night, she heard the voices of ‘people who are dead’. When asked her name, Mary responded: ‘Queen Victoria’.

One week after admission to the cavernous institution, Mary did not know where she was: ‘Says she is in the ambulance’. Two weeks after admission, Mary could not remember her doctor’s name and reported hearing ‘voices going about. Does not know what they say. Restless’.

Over a year later, Mary was still in the asylum and was described by the doctor as ‘very dull. Does not know who I am or where she is’. Nonetheless, Mary did ‘a little work’ on the ward, probably needlework or laundry. The following January, after two years in the asylum, Mary’s six-month review by the doctor was even more terse: ‘Dull, stupid. Will not answer a single question. Works.’ In July, the doctor ‘couldn’t get a word out of her, only a foolish smile’.

Three months later, the clinical notes recorded that Mary was ‘dying of phthisis’ (tuberculosis, which was common in the large, unhygienic asylums). Later that month, Mary’s sister wrote to her from England:

My Dear Sister,

I hear from the doctor that you cannot live long. I am not surprised as it was the opinion I formed of you when I saw you last August. Now, what I want to know is, is there anything you would like that you can’t get in hospital, I mean in the way of fruit or cakes? If you will let me know I will send you some money. I am sure any of the nurses would get anything. I will not say I am sorry you are dying. The wonder to me is you have lived so long, considering what you must have suffered the last 10 years in poverty in Dublin.

Hoping you will have a happy death, if you are not already reaping the reward of all your sufferings here,

Your affectionate sister,

Jane.

In Mary’s medical file, the doctor recorded that Mary’s ‘sister sent her the appended letter which I did not give her’. At the time, it was common for doctors to withhold letters that might upset patients, even at the end of life.

Like so many others, Mary died in the asylum, just a day or two after her sister’s letter arrived, having spent the last three years of her life in Grangegorman. Apart from the presence of the asylum staff, Mary died alone, abandoned by her family, her community and a society that offered only cold institutional comforts to the destitute mentally ill.

How did people like Mary end up in this hopeless, tragic situation? And why? And what were the final years of Mary’s life like, behind asylum walls?

These are the questions that inspired this book.

The mental asylums are Ireland’s awkward institutions. They were designed to treat and contain the mentally ill but soon assumed a life of their own: meeting the complex needs of troubled families (often unrelated to mental illness); alleviating social problems in surrounding communities (especially during times of poverty, famine or political unrest); and—possibly most of all—supporting local economies by employing tens of thousands of people, often in areas of the country with limited alternative employment.

Ireland’s enormous asylums were secular institutions, run by government, so it is not possible to place responsibility for them with the Roman Catholic Church, which is commonly associated with many of the other excesses of Ireland’s institutional past. The church never became deeply involved in the asylums, its attention occupied, perhaps, by its extensive involvement in general hospitals, maternity care, schools, orphanages and laundries. Or perhaps the mentally ill were seen as undeserving? In any case, the story of the Irish asylums is more complex and troubling than any simple explanation permits, and does not lend itself to easy exposition.

Even the language we use to discuss the asylums is contested and uneasy. Acceptable terminology moved from ‘lunatic asylums’ to ‘district asylums’ to ‘mental hospitals’ to ‘psychiatric institutions’ and, finally, to ‘inpatient mental health units’. People suffered from ‘madness’, then ‘lunacy’, then ‘psychiatric illness’ and now ‘mental disorder’. And there were, at all times, a range of other, less acceptable and frankly offensive terms. In all respects, the story of Ireland’s asylum system is an awkward, complex, contested and unresolved one.

But it is also a story about well-intentioned efforts to care for the mentally ill, house the destitute, accommodate the intellectually disabled and provide some kind of ‘asylum’ to people whom Irish society was only too ready to label as odd, different, ‘other’.

As a result of these competing complexities, the history of the Irish asylums can be explored in many different ways: by examining the process of negotiation that resulted in so many admissions occurring in the first place, by telling the stories of any of the numerous hospitals that were required as a result, or by presenting the alarming statistics of the asylum system as a whole, as Ireland built and filled more asylum beds per head of population than any other country in the world.

These are the stories that fill this book, to varying degrees. But this is primarily a book about people, telling its story through case histories drawn from the archives of one institution, the Richmond District Asylum in Grangegorman, Dublin, the establishment that lay at the very heart of Ireland’s network of institutions for the mentally ill and provided the example for others to emulate. The Richmond was where new treatments were introduced, new ideas developed, and more patients treated than at any other asylum in the country. For better or for worse, the Richmond, also known as ‘Grangegorman’ and, later, ‘St Brendan’s Hospital’, set the tone for Ireland’s mass institutionalisation of the mentally ill throughout the 1800s and much of the 1900s.

The stories are both extraordinary and disturbing.

In the late 1850s, for example, four decades after the asylum opened, Máire A., a 23-year old single ‘servant’ was admitted to the Richmond. Máire was transferred from the neighbouring Richmond Penitentiary (prison) and diagnosed with ‘melancholia’, cause ‘unknown’. On admission to the Richmond, Máire’s ‘reaction to questions’ was ‘fairly prompt and coherent’. She was ‘not devoid of intelligence’ but had ‘a slight tendency to hypochondriasis’.

The medical notes record the stark circumstances under which Máire was declared a ‘dangerous lunatic’ and committed to the asylum:

She describes clearly the incident of her brother asking her to come for a walk with him and then taking her to the police office. Her hair was shaved off and she was detained in the jail. After some years she was transferred here. She says that previous to her arrest, something very terrible was in her and wouldn’t let her rest in the bed and made her break a window. She speaks as if of some force possessing her, though she denies that it was the devil.

In the asylum, Máire was ‘an industrious working patient for many years’. She was ‘very tidy and respectable in appearance’, with ‘mild chronic melancholia’.

But despite the ‘mildness’ of Máire’s diagnosis, despite her good conduct, and despite her industriousness in the institution, she was to spend the rest of her life in the cramped, crowded wards of the Richmond: devoid of personal possessions, utterly deprived of privacy, with straw for bedding, and with no control over her daily routine. Máire took her meals in vast, noisy dining halls, washed in communal bathrooms, and slept on wards that were crowded, disturbed and often dangerous. With wearying inevitability, Máire eventually died in the institution, succumbing to ‘heart disease’ at the age of 68, some 45 years after she was first admitted.

Máire’s story was not an unusual one in Ireland or elsewhere during the nineteenth century. But while many countries established asylums for the mentally ill during this period, Ireland’s rate of admission rose faster than those in other countries, was higher at its peak, and was slower to decline.

How did this happen?

‘Asylum: Inside Grangegorman’ by Brendan Kelly is on shelves now, or available from the Royal Irish Academy website for €18.95

Photography by Conor Mulhern. Illustrations by Fidelma Slattery.