By Bill O'Sullivan

17th Feb 2014

17th Feb 2014

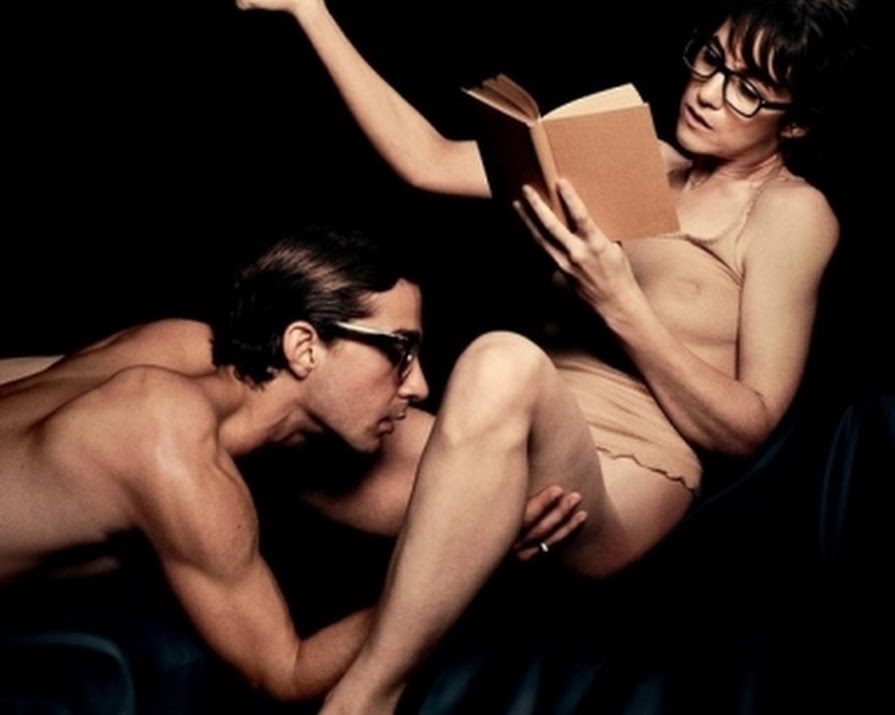

“Forget about love” runs across bottom of the Nymph()maniac posters with the ‘O faces’ of some of Hollywood’s finest filling the vignettes above. Like most of the clever advertisement and tongue-in-cheek tactical marketing that has surrounded the film’s release, the poster would have you believe that Lars von Trier’s much-hyped movie is about the more brutal and de-romanticized aspects of sex. But it isn’t. Or rather, it is and it isn’t. Whilst it is one of the most graphic, grueling and garrulous sexual epics you are ever likely to see in the cinema, it is also a dark and immersive journey into the ferocious cacophony of emotions that are related to sex. The dank fungal feelings and thoughts that we dare not face straight on, are what we return to recurrently via the sex scenes. We meet Joe, (Charlotte Gainsbourg) as she recovers from a violent attack under the watchful eyes of a priest-like Seligman, played by a mannered and pitch perfect Stellan Skarsgard. In form of recovery Joe takes it upon herself to explain how she has ended up in her current circumstance, and so begins the story of a life-time of sexual exploits – perverse, tender, disturbing and defying.

There is no getting away from the sex in Nymph()maniac – it plies open the viewer’s eyes and seeps into the mind, trickling down the walls of the unimaginable. What von Trier does is carefully arrange all the psychologically violating elements that are not the sex itself, into small thought-bites throughout. This is perhaps done to greatest effect with Bach’s music, where an explanation of the Fibonacci Sequence accompanied by solemn organ music, evolves into an analysis of three different types of sexual partners. The result is a work filled full of stunning set pieces, moments of such a transcendent poignancy and beauty, that it is hard to imagine how all the elements can coexist so seamlessly within the same movie. Von Trier picks our basest fascination and uses it to his own advantage to explore the themes of intimacy, family, social responsibility, gender, consumerism and love. And he does so via the medium of sex. It is as subversive and countercultural as one would hope. Yet what is under scrutiny is not society or culture (as for instance was arguably the case with Steve McQueen’s Shame), but far more terrifyingly it is the existence of anomaly, ‘the anomalous’ in everyday life that he is interested in. It is no surprise then that at one point Edgar Allan Poe is introduced as an element (who famously coined the use of the ‘uncanny’ in his genre of short stories), and whose death by delirium tremens is referenced, a condition in which ‘reality is no longer distinguishable’, and everything turns into incomprehensible horror until death.

We withhold further judgment til Volume 2. Volume 1 opens February 28th in the IFI

Roisin Agnew @Roxeenna