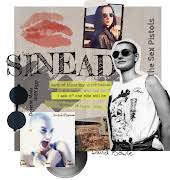

By Meg Walker

10th Jan 2019

10th Jan 2019

When everything else in life was out of her control, Jacqueline O’Mahony turned to writing – something she understood and knew would set her free.

I was 34 when my son, my first child, was born: not old, but not young, either. I’d spent my twenties studying, and then working, in Ireland, in Italy, in Spain and America and – finally – in London. I turned 30 in London, and began to become interested, then, in numbers, in equations: if a woman in her early thirties, of good health, has her first baby by, say 34, how old will she be when she has her second baby? Challenge question: what are the chances of her having a third baby? For extra points: what are the chances, in percentages, of something going wrong with those pregnancies? What are the odds? And are those odds worth taking?

The odds of something going wrong, it turned out, were high in my case. I had my daughter at 38 – within waving distance of 40 – and she was born by emergency C-section, three weeks late. She had severe feeding difficulties for the first year of her life, and had to be fed tiny amounts every two hours, day and night, for months. Oh, the numbers: millilitres of formula, measured out. Days broken down into hours, into minutes. Baby’s growth faltering, her numbers dropping.

I had never been good, really, at maths. I had never even liked numbers, I thought wildly, one long, dark night as I struggled to feed my baby. But I’d been good at English: I’d done a PhD; I’d worked for years as a journalist. I would begin, I determined, to write something. The day after that long night, I wrote a line. The day after that, I made myself write a little more. And so the writing grew. When I wrote, I was in control; all was ordered, and contained, on the page, and I kept writing, and the writing kept me going. My daughter began to grow stronger, and when she slept – for up to four hours now, because she could feed a little more – and if my son was asleep at the same time, I wrote, and I wrote.

I was writing a book, I realised, after some months, about a woman who’ll do anything she can to survive, and as the book grew, my children grew, and one experience fed the other, and became bound up with each other. We were surviving now. We were, almost, thriving.

I began to feel that maybe we had defied the odds – that we had luck on our side, that the numbers had worked out for us, after all.

I was 41 during my third pregnancy. A miracle pregnancy. But at the 12-week scan, the numbers, suddenly, stopped adding up. The baby wasn’t growing properly. The lines on the graph were all wrong. At 16 weeks, the baby stopped growing.

I was 42 during my fourth pregnancy. This time, when the numbers ran away from us during the early – emergency – scan, we knew what it meant. The baby stopped growing at 12 weeks.

I was 43 during my fifth pregnancy, and those were numbers that did not add up at all, did not belong, even, in the same sentence. Consultants shook their heads when they read my notes. The odds, I was told, were so against me now that they were beyond reason, beyond logical calculation.

I kept writing. On a good day, a thousand words at least, 500 on a bad. Those were numbers I could count on. The book was chapters long. It had a life of its own. My body was a foreign place to me now; I could do nothing to bend it to my will. I could do nothing but wait, and see, and count down the days, and try to make the numbers work – I went over the same calculations again, and again, each time hoping for a different outcome. If they have to deliver the baby at six months, I would think, and she weighs, say, three pounds, what are the percentage chances of her developing normally, of surviving even? Why had we taken such a chance? Why had we thought we could beat the numbers?

The book, however, I could shape as I wanted, and in the writing of it I was set, almost, free.

I was hospitalised at seven months. None of my numbers made any sense anymore, to anyone. I sat in my hospital bed, in the permanent twilight of my small, lonely hospital room, and wrote – I finished the first draft of the book hooked up to machines keeping track of my disappointing numbers. When the numbers made it too dangerous to wait any longer – we are looking here, the consultant told my husband, at a potentially fatal situation – my daughter was delivered, by emergency C-section, five weeks before her due date.

She made it. Her numbers, the doctors said, were fine. And I finished the book. Would I have written it if life had been easy, worry-free? No, I think. The pain became a hammer I used to beat out the writing.

In the dark times, you have to work your way towards the light.

Jacqueline O’Mahony’s debut novel, A River in the Trees (Riverrun, €16.99), is out now.

Portrait photograph by Nicola Megan.

This article originally featured in the December 2018 issue of IMAGE Magazine.