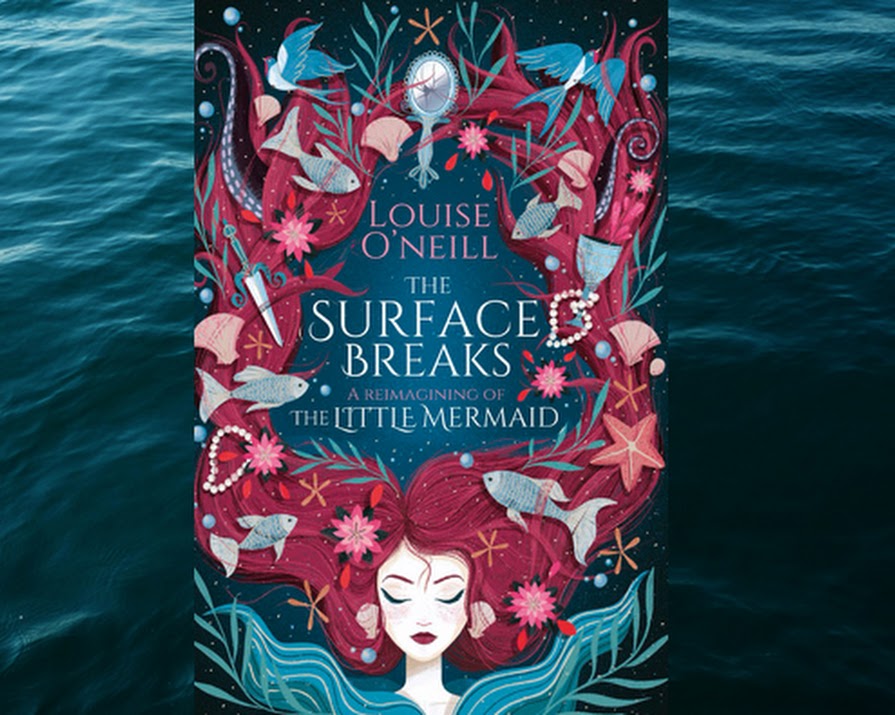

The Surface Breaks by Louise O’Neill: prepare to wonder about the stories you tell your children

By Lia Hynes

02nd May 2018

02nd May 2018

The Little Mermaid is of course based on the famous 1837 Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale of the same name. Now, it has been given a rewrite, a feminist reimagining through the eyes of Irish author, Louise O’Neill. The original is a bleak little story- mermaid, whose most distinguishing characteristic is her beauty, falls in love and makes a bargain with a witch in order to lose the tail and gain legs. In doing so she agrees to everlasting pain when walking, to losing her voice, and never seeing her family again.

Unfortunately, the object of her affections, her Prince, views her as a sort of amusing plaything and eventually marries someone else. She is spared the death her bargain should have condemned her to. Instead, after three hundred years servitude, she will be given an immortal soul, a climax with a religious undertone of the punished fallen woman that is deeply depressing.

Louise O’Neill’s version is no less grim. The bones of the story are the same as the original. Gaia, as she is named in O’Neill’s version, is the youngest daughter of the Sea King, a controlling tyrant who values only conformity, beauty and obedience from his daughters. In Andersen’s fairy tale the little mermaid’s mother was but a footnote; here, having mysteriously disappeared on Gaia’s first birthday, she is one of the main motivators behind her youngest daughter’s restlessness.

There is an underlying sinister brutality to the mermaid’s world, conjured up by O’Neill’s visceral writing. As a sign of their status, the mermaid’s tails are viciously studded with pearls, which pull at “tendrils of flesh”. Gaia’s fiancé is a war-obsessed older man who sees his betrothed as merely another conquest: “it is as if he wants to peel my skin away from my body and taste it on his tongue”. At a moment of emotional distress, Gaia imagines her throat becoming full of teeth.

As well as an obsession with finding out what really happened to her mother, Gaia’s fate is sealed by her conviction that there must be something better than this. She dares to “look up”. Sleeping in a roofless tower she peers up through the water above, questioning the ways of her male dominators. Allowed to visit the surface for the first time on her fifteenth birthday, Gaia’s feelings of discontent and fear crystalize when she rescues a young man, Oliver, who becomes the object of her obsession.

The most enjoyable example of O’Neill’s rewriting is in the case of the witch, in the original a classic crone, unrelentingly haggard and disgusting; at her first appearance she is depicted with a toad eating from her mouth. Here, Ceto, is a charming, unapologetically self-loving powerful woman, who has flouted the conventions of the Sea King’s rule to live how she pleases, and to ignore his stringent beauty standards. She is curvy. She wears lipstick. “I did not know such a body was even allowed to exist,” Gaia marvels.

As is often the case with the main female characters in O’Neill’s writing, Gaia attempts to lose herself in a male. Told by her society that in so many ways she is wrong – too loud, too thoughtful, too sexually aware, too angry, too hungry, too much, she looks outside herself to soothe her unhappiness. Escape from the domination of her father is only possible through attaching oneself to another man. As always the plot and pacing are masterfully handled – it is common to be told an O’Neill book was consumed in one or two sittings. This is ostensibly aimed at the YA readership, but its themes will speak to women of all ages.

As a storyteller, one of O’Neill’s great strengths is to shine a light on things as if for the first time. Her writing acts as a snow globe, throwing everything in the air. When it lands, it is the same world, but seen ever so differently. Accepted social norms suddenly become shocking, as she outlines for us through her sharp, incisive writing how wrong are the ways we have never even questioned.

The Surface Breaks is the kind of allegorical, message-driven writing which is perfectly suited to a childhood legend we are already familiar with. That’s how you saw it before, O’Neill says, but now look again, closely. The fantastical world of the little mermaid softens what in fiction based in reality, or in the hands of a less talented storyteller, could be heavy-handed.

This is not a comfortable read but it is a compelling one. There’s a sort of facepalm quality to it. Of course, you think. Of course this is what happens to the powerless princess whose entire existence is predicated on her looks.

O’Neill may not offer the traditional Disney married-ever-after ending, but you will be consumed with knowing how things turn out for her little mermaid. And she will make you wonder about the stories we tell our children, how many turn on the heterosexual happily ever after. The internet is currently awash with speculation that in Frozen 2 Elsa will come out as a lesbian, and find a girlfriend. It would be nice to have more stories for children that simply did not involve a romantic love story as their central plotline at all, but the first openly gay woman in a Disney blockbuster would be progress of sorts. As always, O’Neill has created a book that will have you thinking, and talking, for days.

The Surface Breaks, a Reimagining of The Little Mermaid, by Louise O’Neill, Scholastic