By IMAGE

18th Jul 2018

18th Jul 2018

Hindsight, as they say, is a great thing. In a post-#MeToo world, EMILIE PINE reflects on the times she wishes she spoke up against the men who took advantage of their power over her, but it wasn’t so easy to do at the time.

I’m a pretty loud person. I get asked to make announcements at events because I can be heard above the din. A friend of mine once told me I barely needed a mobile phone because I could just shout and be heard from miles away. And I’m loud in other ways too. I speak up at meetings, I contribute to discussions, and hey, get this, my job as a lecturer means that I talk for a living. But you can be silent and loud at the same time, it turns out.

While I was a PhD student, I found myself in the “grey area” of sexually inappropriate advances. And the first time it happened, though it makes me sick to admit it, it did not occur to me to object. A professor, whose work I revered, attended a paper I gave at a conference and afterwards, in the bar, he beckoned to me, then led me by the hand behind a pillar, where we were shielded from view. Still holding my hand, his other arm rubbing against my side, he told me he wanted to be alone with me to talk about my career. Improbable as it seems now, I felt lucky to be singled out, and I felt that his attention was benevolent rather than sexual.

Okay, maybe that’s not the whole story. I knew it was sexual, I knew he shouldn’t be doing it, I knew I shouldn’t smile in response. But I did smile and here’s why: it was my first conference, I was young, he was powerful. I was trying to play the game. Serendipitously, the conference organiser appeared before anything further could happen.

Another encounter, a few years later, with another man made me begin to question just how benign a man’s attention at work could be. He was a lecturer in another department and I was in my final year as a student. I lived in student residences on the university campus. Before that day, I had always thought that living in my workplace was convenient – it had never occurred to me that someone saying a couple of sentences could suddenly make it feel perilous.

One afternoon, as I came out of the gym, this lecturer was walking past. Seeing me, he stopped to say hello. He was only a few years older than I was, yet his job put him in a power category above me. He seemed to want to talk, but I was flushed from the exercise class, and embarrassed at being post-workout and pre-shower, so I apologised and said I had to go “clean up”. I can still feel the cold air and how my sweatshirt stuck to my skin and chafed on my neck. And then he said: “I like to see you sweaty.” I didn’t really respond, I just turned to go, at which point he commented that he liked “the view from the rear”. And then he walked behind me all the way to my building.

It was daylight and there were plenty of other people around. Perhaps I shouldn’t have felt threatened, but I did. I got to my building, and stopped, key in hand, turning my head to see if he was still there. Ahead of me, a narrow corridor led from the building’s entrance to the door of my room. I did not want him to follow me into that corridor. He waved as he walked past. I ran in and double locked my door behind me.

The next day, I described the exchange with the lecturer to my boyfriend and best friend. They didn’t really know what to do or say. I sat at my computer and opened a “compose email” box, thinking I would write to someone about what had happened. But then I paused. How would I phrase it? Who would I send it to? Who would take it seriously? And if someone took it seriously, what would happen then? I could imagine only too well the lecturer’s response to my complaint – that it was a joke, that it was a compliment, that he was only being friendly. And I knew that if I claimed that it had not been a joke, that it had been an unwanted come-on from a lecturer to a student, I would suddenly be labelled the trouble-making girl who couldn’t play with the big boys. I knew the price of sending that message. And so I deleted the email.

I am not claiming that either of these events were damaging long-term – I was not traumatised, nor was my career impeded by either of these men’s come-ons. Nevertheless, I was shaken – shaken because I was suddenly made to confront, and to be ruled by, the unspoken code of the workplace, where inappropriate comments and the invasion of women’s personal space are recognised as wrong and yet also acceptable.

In the end, it’s not the arm-stroking or the predatory comments that are the real offence. It’s that instead of blaming those two men, I blamed myself. I blamed myself for somehow provoking their interest. I blamed myself for making a big deal out of what I knew was so commonplace it barely registered as out of order. And I blamed myself for not speaking out. I took on all this blame because I imagined that it was my responsibility as a woman to regulate and gate-keep sexual exchanges with men.

I learned through these encounters that the most important skill for working women is resilience. This resilience has allowed me to “rise above” the sexist work culture that I have repeatedly encountered over the past two decades. But resilience, while it allows personal survival (and even success), does not challenge the larger toxic culture. And it does not stop the problem of unwanted sexual advances. And it does not produce what we really need – a culture of respect and consent.

In a post #MeToo world, I know that my resilience was a kind of silence. In the context of what so many other women have shared as part of this movement, I also realise that my experience is minor. But as #MeToo has also shown me, minor problems are still problems, and harassment at the bottom of the scale is still harassment (no matter what the backlash wants us to believe).

I know that there may be negative reactions to my decision to share these experiences, not least because they happened so long ago. But the time-lag is part of my point. Since I’m no longer a student, I can speak up with very little personal or professional risk. I tell my story not because my experience is exceptional – far from it – but because for so many women and men who are precariously employed, or dependent on goodwill, calling out harassment is still not possible. It’s important that we tell our stories – minor and major – because that is the first step towards changing the culture. And out of that cultural change, we can create policies that will mean we can all go to work free of the burden of blame and without needing the armour of resilience.

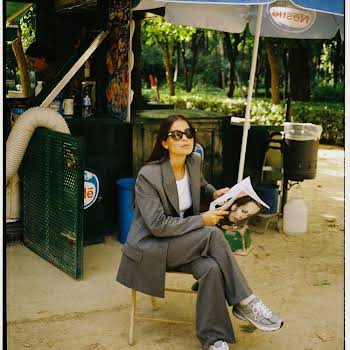

Notes to Self: Essays by Emilie Pine (Tramp Press, €15) is out July 19. @emiliepine

PORTRAIT BY RUTH CONNOLLY