By Sophie White

15th Apr 2018

15th Apr 2018

A recent study has sparked a series of polarising articles around the treatment of mental illness with psychiatric medicine which suggests we’re still not getting it right when it comes to the drugs

The happy pills have been under the microscope a lot in recent weeks. Hot on the heels of the result of a six-year study investigating the efficacy of a dozen ‘new generation’ antidepressants being published in the Lancet, was an in-depth New York Times feature which revealed a group of users finding withdrawal from longterm use of these same drugs almost unbearable.

The perception-altering aspect of psychiatric medicine has meant that for generations they have been a divisive subject. The Guardian reviewed the findings of the Lancet study and declared “The Drugs Do Work” in a dangerously definitive headline. And here is the problem with definitive declarations when it comes to medication. Outcomes will always be variable as soon as the medication comes into contact with the individual.

Recent Netflix documentary, Take Your Pills which largely focuses on the (over?)prescribing of Adderall (traditionally used to treat ADHD but rapidly becoming a study aid for a generation of young Americans) made the point that in actuality there are no such things as side-effects as such but rather effects, some of which will manifest in a welcome way and some which won’t. A reaction to a drug will be completely unique to the individual taking the medication and as with many types of medication the risk of adverse effects is offset against the potential benefits to the individual suffering.

The problem with psychiatric drugs is that there has long been a suspicion of these medicines, a suspicion drugs used for treating other illnesses (that may also have unpleasant attendant effects) have not attracted to the same extent.

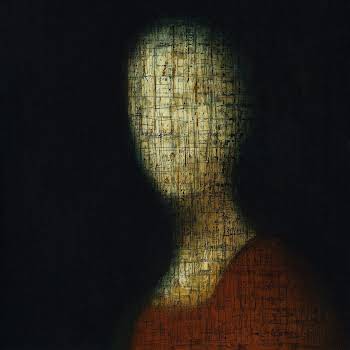

Pharmaceutical intervention has often been portrayed in popular culture in a very negative way, we have seen drugs that will cloud your brain, cause flat affect and rob patients of their individuality in One Flew Over The Cuckoos Nest and Girl, Interrupted. However, what is often overlooked is that many of these depictions are of an older breed of pharmaceuticals that were significantly less refined.

Another issue is the perception of the field of psychiatry in general. A 2010 study found “The public image of psychiatrists is largely negative and based on insufficient knowledge about their training, expertise and purpose. For example, it is not widely known that psychiatrists are medical doctors, and the duration of their training is underestimated.”

On the other side of the approach to treatment of mental illness is “lifestyle measures” which to the ears of a person suffering from a significant and, most likely, terrifying episode sounds like a joke. A bad one. When you are fighting to survive each day and fearful of the harm you might cause yourself, suggestions like “going for a walk”, “getting some me-time” and “cutting out sugar” sound laughable. For many people with mental illness, the pills in conjunction with intensive monitoring and therapy is the only hope of getting to even a reasonable baseline of mental health in order for lifestyle measures to be achievable, never mind effective.

Writing in a recent column in the Evening Standard in response to the Lancet study, Emily Sheffield described two instances of being prescribed antidepressants without the appropriate complimentary therapies:

“About 65 million prescriptions a year for antidepressants on the NHS don’t seem to point to any reluctance, rather a gay abandon in handing them out,” writes Sheffield. “That they can work better than a placebo is welcome, but a third of those who take them will not respond at all; the study did not take into account the impact of side-effects on patients. Nor did it explore their efficacy long-term. Depression is often triggered by environmental factors. A pill cannot cure life. It can help pull some out of a mental nosedive but it will not provide the tools to prevent the same factors striking again.”

The biggest baggage the antidepressants must shed is the over-prescribing and under-monitoring epidemic that we saw rise in the 90s in the United States and described in popular fiction like Prozac Nation. Cultural representations like these are what made me refuse psychiatric medication for three agonising months before suicidal feelings set in and I realised that I needed to try the pills. This was more than 10 years ago and the stigma around mental illness was much more evident than I feel it is today, though that stigma is sadly still present. Mariah Carey just this week opened up about hiding her diagnosis of bipolar II disorder such was her fear of backlash.

“Until recently I lived in denial and isolation and in constant fear someone would expose me,” she told People magazine. “It was too heavy a burden to carry and I simply couldn’t do that any more. I sought and received treatment.”

Carey’s admission highlights something many people with mental illness echo: that the stigma of the experience is often as bad or worse than the actual presentation of the illness.

Many are still reticent about their medications. I didn’t realise I knew anyone taking antidepressants until I opened up myself. I think a certain amount of ambivalence towards antidepressants is understandable, their branding has always been off in my opinion. The ‘happy pills’ image could not be less accurate if you ask me a veteran user of the so-called happy pills. The ‘happy pill’ suggests an instant fix which is far from the truth, many of these medications need to build up in the system before benefits will be felt and other attendant effects may be unpleasant. In the US and New Zealand, pharmaceuticals are advertised freely which has surely impacted the rate of consumption and muddied the perception of these pills as verging on a consumer product like Levis or froyo, when in fact they are powerful medications that require strict supervision when being administered.

Lexapro was an antidepressant I used for three years after a drug-induced nervous breakdown in my early 20s. I was also prescribed an anti-psychotic called Olanzapine (commonly used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder) at the exact same time. I was monitored by my care team extremely closely during this period. The side-effects I experienced were certainly unpleasant (a mouth perpetually dryer than the Sahara, shakes and ticks, insomnia, racing heart, loss of appetite, flattened mood and decimated libido) but no more unpleasant than a persistent sense of disassociation and unreality, auditory and visual disturbances and feeling suicidal, I had been battling before.

There is no definitive answer to this debate, antidepressants have caused extreme reactions in a small number and have no effect whatsoever on a larger number. For some who suffer from a chronic mental illness, a previously effective treatment may suddenly cease to be therapeutic – comedian, Sarah Silverman recently spoke publicly about this issue – and for others tapering off will be a trying and draining experience. Is any of this better or worse than the experience of the illness itself? It is hard to say but what does need to be said over and over again is that expecting miracles from pills is dangerous, as is taking them in isolation without appropriate supervision and complementary treatments.