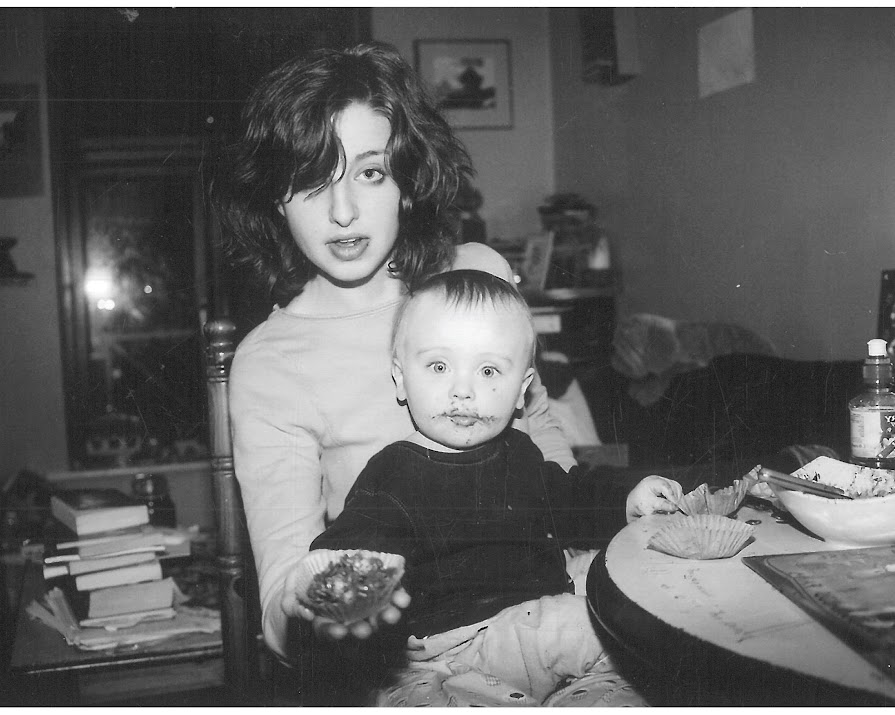

“You’re weird Mammy… other mothers iron”: Author Elske Rahill on writing and motherhood

By IMAGE

14th Mar 2021

14th Mar 2021

“Every baby costs you a book” – that’s something women writers hear a lot. Author and mother-of-four Elske Rahill argues that creativity and motherhood don’t have to be either/or choices.

“You’re such a weird mother, Mammy.” My 13-year-old is sitting at the kitchen table, cutting into an uncooled carrot cake and smiling a smile I can’t quite read.

“Am I?”

“Yes, Mammy. You are. You’re a good cook, though. Nice cake.”

“Thank you. How am I weird?”

“You just are. You know you are. Other mothers iron and stuff.” The comment was brought about by talk of peanut butter icing, but I find myself immediately blaming my career for this non-ironing weirdness. The attributes of a writer are rarely associated with ideal motherhood, and this may cause me more anxiety than I realise.

By the time I was a teenager, I knew I wanted to write, and I remember assuming that this meant no children. Jean Rhys – who I loved – is said to have allowed her first child to die from neglect and to have left the second; Virginia Woolf was famously childless; and, although she wrote beautifully about babies, Sylvia Plath’s suicide absented her from her young children’s lives – these were hardly advertisements for the writer-cum-mother.

The pram

Cyril Connolly famously claimed that “there is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hallway”. When I Googled the phrase, I was met with a proliferation of so-titled articles from writers who are mothers. They all seem to be saying pretty much what I feel: that the roles of mother and writer are not mutually exclusive. Then again, they would say that.

When I was pregnant with my first child (the one who just called me “weird”), I was still at university, and I wasn’t sure what this baby meant for my future. I spent a few weeks selling “massage cushions” at a stall in Debenhams. This was during the boom, so the (utterly useless) cushions sold themselves, while I sat reading Anne Enright’s Making Babies. I remember the part where she explains the choice to wait until she had “got somewhere” before having children. It was the last thing I wanted to hear. By then I knew of some mother-writers like Toni Morrison and Elizabeth Strout – women who were published when their children were “a bit bigger” – Tillie Olsen, for whom housework and earning meant a long hiatus from writing. There was Margaret Atwood – she had one child. Maybe, with only one, I’d be alright…

“Motherhood was like entering a new world, it blew open everything I thought I knew. Writing became a matter of urgency.”

A baby for a book

A year later, in the small hours of the morning, baby finally asleep, I wrote In White Ink, the first story I was very happy with. I was young, single, and very scared of what the future held, but it was also a wonderful time; motherhood was like entering a new world, it blew open everything I thought I knew. Writing became a matter of urgency. I can’t imagine how that time would have gone, if I hadn’t written my way through it. I also can’t think of anything that inspired me more than that experience.

“Every baby costs you a book” – that’s something women writers hear a lot. Until I was pregnant with my fourth child, I didn’t think the rule applied to me. For me, writing and babies were too entwined to be part of an either/or economy.

The cost

But 12 years and two sons later, I became pregnant with my daughter, and I began to fear the saying was true. I was so sick that some days I couldn’t stand up. I couldn’t read. Any writing I did was in the Notes app on my phone, and usually provoked a new bout of vomiting. It didn’t get better after the first trimester. My short story collection came out when I was about four months pregnant, and at the book launch, I could hardly stand up.

I was seriously pleased with myself for being invited to Woman’s Hour, but the morning of the show, I could hardly make it into the taxi. They take a mug shot before you go on and post it on Twitter. I couldn’t smile, I was so frightened of vomiting. I had to bring a sick bag into the interview with me. Afterwards, I saw from the Twitter photo that I had turned up with my jumper on back-to-front.

I told my publisher I couldn’t deliver my next book until I had delivered this baby. There was simply no denying it – that pregnancy cost me a year of writing.

The horrible sickness for those ten months made me think a lot about the body, about what it means to be a woman and a mother and how we are forced to confront our mortality in such a direct and visceral way. It made me think about my grandmother. Of how hard it is to negotiate the body’s limitations, to accept our dependency on it. Having a daughter also made me think of motherliness in a new way. And these are some of the things my next novel, An Unravelling, is about. I think it is a stronger – if later – book because of that experience.

The thick of it

Three contemporary Irish mother-writers immediately come to mind: Lucy Caldwell, Caitriona Lally, Belinda McKeon, who gave birth to her second child the same week her play Nora premiered in Dublin.

Is it thanks to the affordability of white goods that women now seem to be writing from the thick of maternity?

Is it that fathers have started to share the labour more? Or have readers grown more interested in the cut and thrust of a life lived in the body, the savage truths that play out in reproductive and domestic life?

Cyril Connelly wasn’t a mother, and his “pram in the hallway” symbol falls pretty short of the experience. I have four children, and I don’t write with the baby in the hall, or even the crib. Often, these days, I write with the baby on the breast, a cup of coffee on the bedside table, my laptop on my knees.

“Do you think if I wasn’t a writer, I would be less weird?” “What are you talking about, Mammy?” It’s a nonsense question, really. It is like asking who I would be in a parallel world. If I wasn’t writing, maybe I would do something else, something more moral, something less demanding, or something that earned enough money to get a “girl” in every Tuesday to do the ironing…

Elske Rahill’s novel, An Unravelling (Head of Zeus, approx €10) is out now. This article was originally published in the June 2019 issue of IMAGE Magazine.