By Erin Lindsay

28th Apr 2020

28th Apr 2020

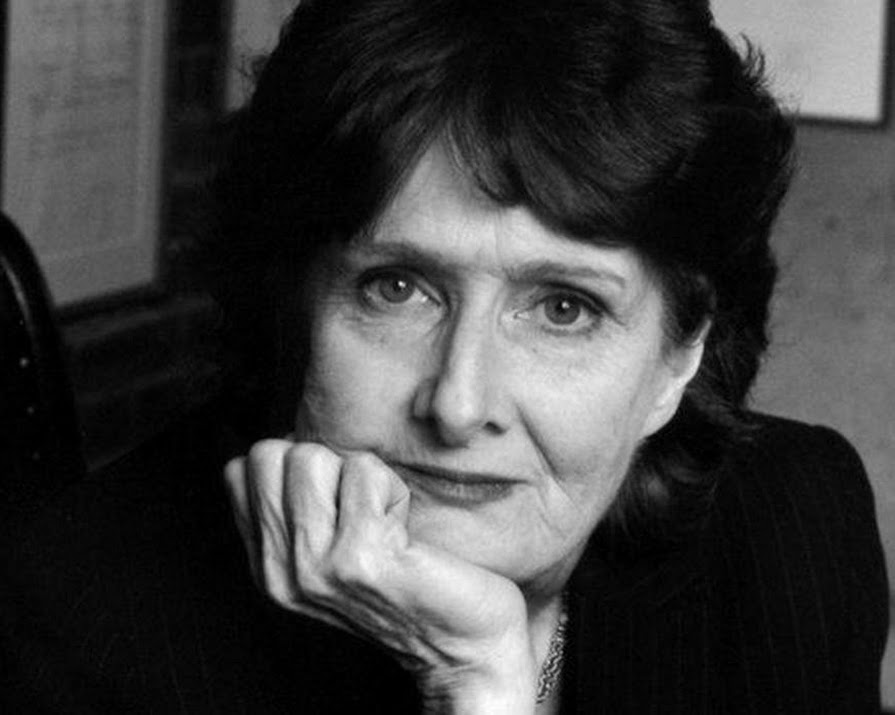

Eavan Boland, throughout her poetry career spanning over four decades, laid the life of the Irish woman bare for the world to understand and appreciate

Poetry lovers across the country, and the world, were saddened yesterday to hear of the passing of one of Irish literature’s premier female voices, Eavan Boland.

Boland died at her home from a stroke, aged 75, and is survived by her husband and two daughters.

Boland’s poetry delved into the lived experiences of women in Ireland — their domestic lives, their insular lives — allowing all that that entails to be revealed to the reader. Understandably, her works were universally appreciated and still well-known to this day, as Boland’s poetry appears on the Leaving Certificate English syllabus to be discovered by new generations time and again.

Here, we’re looking back at some of Boland’s most trailblazing moments, and where her work fits into Irish literature and history.

When her words were used to ignite a new nation

In 1990, the country looked on as our first female President Mary Robinson addressed the nation, thanking its people, and most especially its women, for electing her to lead the country into a new age.

It was fitting that Robinson, who was friends with Boland from their time at Trinity College together, quoted Boland’s poetry in her address, saying: “As a woman I want the women who have felt themselves outside history to be written back into history, in the words of Eavan Boland, ‘finding a voice where they found a vision’.”

When a fitting poem for our current times was shortlisted for RTÉ’s Ireland’s Greatest Poems

In 2015, RTÉ began the search for Ireland’s greatest and best-loved poem of the past 100 years, and published a shortlist of 10 poems to be considered. Among them, Boland’s poem Quarantine (a fitting text for our current climate), featured, as a haunting reflection of the 1847 Famine. Read it in full below:

In the worst hour of the worst season

of the worst year of a whole people

a man set out from the workhouse with his wife.

He was walking — they were both walking — north.

She was sick with famine fever and could not keep up.

He lifted her and put her on his back.

He walked like that west and west and north.

Until at nightfall under freezing stars they arrived.

In the morning they were both found dead.

Of cold. Of hunger. Of the toxins of a whole history.

But her feet were held against his breastbone.

The last heat of his flesh was his last gift to her.

Let no love poem ever come to this threshold.

There is no place here for the inexact

praise of the easy graces and sensuality of the body.

There is only time for this merciless inventory:

Their death together in the winter of 1847.

Also what they suffered. How they lived.

And what there is between a man and woman.

And in which darkness it can best be proved.

Her contribution to women’s history, read at the U.N

In 2018, Boland was commissioned by both the Irish government and the Royal Irish Academy to pen a poem to celebrate 100 years of Irish women’s suffrage. The poem, fittingly entitled “Our future will become the past of other women” was read both at the U.N and in Ireland to commemorate the centenary of the occasion.

Her final message as editor of Poetry Ireland Review

In March 2017, Boland took the position of editor of the Poetry Ireland Review, and worked to shape the journal’s artistic direction over three years. Her final issue as editor was published in November of last year, and provides advice for readers and budding poets, that now seems strangely poignant. In her final letter as editor, she wrote:

The life of the poet is always a summons to try to set down some truth that was once true and will go on being true. No poet should have to worry about the public respect, or the lack of it, in which this art is held.

Her career at Stanford University

Boland split her time in her later years between Dublin and Palo Alto in California in the U.S, to serve her career at Stanford University. Boland became a tenured Professor of English at Stanford in 1996, and served as Director of their Creative Writing Programme right up until her death.

Read more: ‘I was a voice’: 10 of the most beautiful lines from Eavan Boland’s poetry

Read more: ‘When I write about Dublin now, I feel like I’m writing about a city that doesn’t exist’

Read more: ‘My accent is a reflection of my home, my family, my experience. I’m learning to embrace it’